Colonial Policies Continue to Influence the Politics in Contemporary India

Shubhro Bhattacharya finds that colonial policies have persistent effects on contemporary politics in India. The land revenue system enforced by the British can be broadly categorised into ‘Landlord Taxation System,’ (or Zamindari System) wherein a local elite was appointed by the British to collect revenues from the village; and ‘Non-Landlord Systems’ where the individual cultivators (Rayyatwari system) or a group of villagers (Mahalwari system) paid the land revenues directly to the British administration. Criminality among the politicians who won the assembly elections from 2004-17 is found to be higher in former landlord districts.

About the Author: Shubhro Bhattacharya is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of Mannheim, Germany. He was a former student of M2 Development Economics at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, from 2021-21 and wrote his thesis under the supervision of Prof. Remi Bazillier.

It was the year 1793. Lord Cornwallis of the East India Company commissioned the landmark ‘Permanent Settlements Act’ in Bengal, which transferred the powers of revenue collection in the ambit of the Landlords of Bengal. In a few years, this system spread to the major regions of Northern India, encompassing the modern day states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. More than two centuries later, this British era Institution had far reaching consequences on India’s quest for development, which has been greatly discussed in various studies and forms the basis of my current research.

There is a rich scholarship that documents how history has persistent effects on the contemporary development outcomes of the countries through its influence on the institutions. In a pioneering set of studies, Acemoglu et al. (2001, 2002) provide cross-country evidence of this persistence. However, as rightly acknowledged in the various studies, the colonial experience for each country basks in a unique cultural, historical and political setting. In a landmark study, Banerjee & Iyer (2005) [henceforth, B-I (2005)] further the enquiry in the same spirit and focus on one specific historical institution in a more narrow setting – the system of land revenue established by the British during their colonial rule in British India (henceforth, India). Starting from the Permanent Settlements Act of 1793, the land revenue system was enforced until India’s independence in 1947. Several decades since, B-I (2005) found convincing evidence of a ‘colonial hangover’ as they observed on 1961-91 Indian Census Data how a multitude of contemporary development outcomes were profoundly impacted by the policies in the colonial past. Thus, B-I (2005) was a pioneering study that attempted to uncover the underlying causes of India’s disparate regional development in the post-independent era.

In a more recent study; Prakash, Rockmore & Uppal (2019) provide clues about a pivotal proximate cause of unbalanced development outcomes in India, as they deploy a regression discontinuity design to find a causal linkage between inferior political selection and underdevelopment in the Indian context. Working on the Politician Affidavit Data of the Election Commission of India from 2004-2008, they find that narrowly electing a criminally accused politician in the State Assembly elections leads to an average 24 percentage point reduction in GDP growth rates (proxied by growth in night light intensities).

With the aforementioned theoretical underpinnings in the backdrop, the key contribution of my research was to identify if there existed a causal association between the proximate and the underlying cause of underdevelopment. More succinctly stated, my research attempts to investigate whether there is a causal linkage between the colonial land revenue system and the incidence of criminality among winners of state assembly elections in the recent elections.

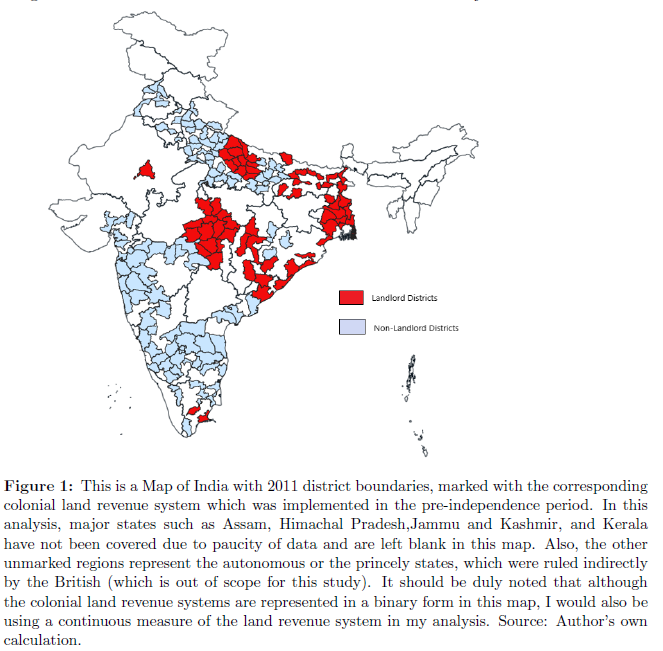

The land revenue system enforced by the British can be broadly categorised into ‘Landlord Taxation System,’ (or Zamindari System) wherein a local elite was appointed by the British to collect revenues from the village; and ‘Non-Landlord Systems’ where the individual cultivators (Rayyatwari system) or a group of villagers (Mahalwari system) paid the land revenues directly to the British administration. B-I (2005) found that those modern day districts, which were governed by the Landlord Taxation system systematically, underperformed in the various development indicators relative to the Non-Landlord districts such as agricultural productivity, health investments, education investments and infant mortality to name a few. In my study, I attempted to document whether this pattern of persistence was also observed for political selection in contemporary India by using the ‘Politician Affidavit Data’ (2004-17) which is provided by the Election Commission of India (and further cleaned and updated by Association of Democratic Reform and SHRUG Data repository).

Former Non-Landlord Districts have Politicians with Lower Criminal Incidence?

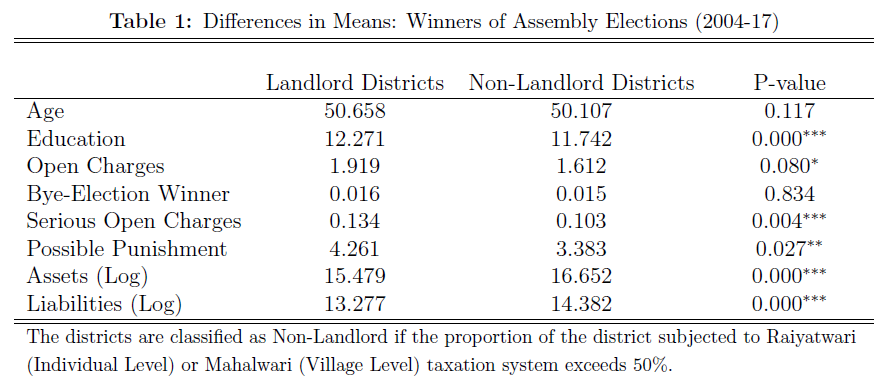

Before answering to the above question, it would be useful to take a cursory look at the descriptive statistics table below which enlists the characteristics of the political candidates from 2004-2017 who won the State Assembly elections.

It should be noted that despite of having a greater level of education on an average, the politicians of the Landlord districts fare worse in the two pivotal characteristics – ‘Open Charges’ and ‘Serious Open Charges.’ In other words, the politicians in the Landlord districts have self-reported higher number of pending criminal charges on an average as compared to their Non-Landlord counterparts.

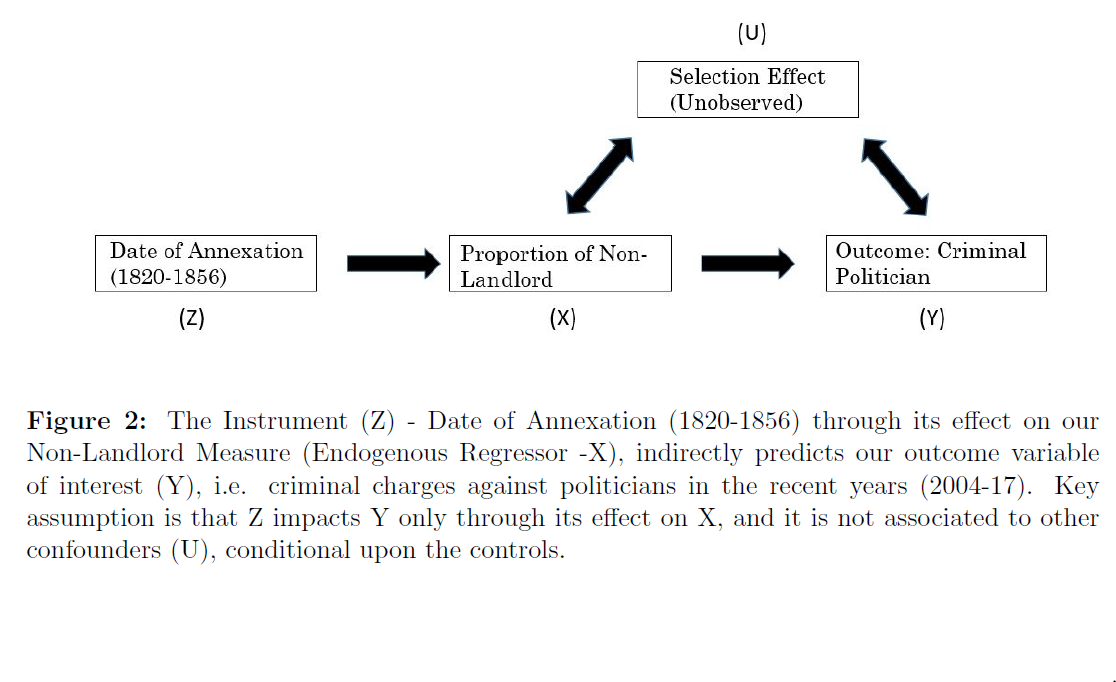

However, the above figures conceal some of the fundamental differences in the underlying characteristics between the two types of districts, which quite conspicuously share their own historical, geographical, cultural as well as institutional differences. I use the Instrumental Variable (IV) strategy in the lines of B-I (2005) to mitigate some of these potential endogeneity issues. The rationale behind the usage of an IV Strategy is to preclude the possibility of a selection bias or in our context, to ensure that our results are not driven by the fact that the form of taxation system imposed by the British were a function of the inherent characteristics of the districts. Thus, we use the instrument – ‘Date of Annexation 1820-1856’ to predict our key explanatory variable, the ‘Proportion of Non-Landlord’ i.e. the proportion of agricultural land, which was not under the purview of the Landlord taxation system. As discussed earlier, the outcome variable of interest was the incidence of criminality among politicians of contemporary India. The entire analysis was conducted at the district level and I obtained historical data on Indian districts from B-I (2005) and Roy (2014), which were then matched with the other explanatory variables based on the 2011 Indian Census district identifiers.

A culmination of factors such as ease of administration, political and economic viability as well as events across the channel (most notably, the French revolution) shifted the proclivity of the British administrators towards the Landlord system in the districts annexed before 1820’s. However, a shift in ideology towards utilitarianism by the influential individual administrators such as Thomas Munro, Holt Mckenzie and Lord Elphinstone, as well as a further consolidation of power over the peasant and working class population (i.e. greater political stability and lower likelihood of an uprising) paved the way for a major reversal in the British taxation policies starting from the 1820’s.

While the above contemplations were essential to argue in favour of the ‘Relevance’ of our instrument, it was also vital to ensure that our instrument has an effect on the outcome only through its effect on our Non-Landlord measure and not directly; or in other words, satisfy the ‘Exclusion Restriction.’ Thus, in both the stages of our IV regressions, a rich set of controls such as Geographic controls, Individual Politician Characteristics, Socio-Economic and Demographic controls at the district level to account for a wide-array of cross-district variations in the observable characteristics. Moreover, as a control for the initial conditions, I also have controlled for some of

the historical characteristics of the districts. Finally, the specification also includes a battery of fixed effects accounting for the State specific characteristics as well as the differences across the Political Parties. Since my benchmark IV Specification is demanding and includes a plethora of controls to account for the differences in observable characteristics of the districts, conditional upon them being exhaustive, the IV strategy seems to be plausible.

I also performed a series of robustness checks such as trying alternative definitions of the dependent variable wherein I only restrict the sample for politicians only facing ‘Serious Charges,’ dropping influential states such as Bihar and West Bengal (the core belt of Landlord districts), restricting the sample to neighbouring Landlord and Non-Landlord districts and finally a placebo test by changing the definition of our ‘Date of Annexation’ instrument.

Across all my regressions, the result was consistent that the former Landlord districts were associated with higher incidence of criminality among the politicians. In the most demanding specification with all the controls and battery of fixed effects, a 1 standard deviation increase in the Non-Landlord proportion is associated with a 0.241 standard deviation reduction in criminal charges against the politicians who won the assembly elections from 2004-17.

Though not straightforward, several mechanisms can be suggested which might provide us with some clues to explain the persistence. First and most importantly, it created an Indian land-owning class, which was given arbitrary powers on revenue collection as well as property expropriation on the masses and were supported by the British administrators. This fuelled a ‘class-based antagonism’ as proposed by B-I (2005) and unsurprisingly, the former Landlord districts witnessed the most violent forms of peasant uprisings and armed violence in the post-independent India. Whereas the above factors ensured inferior initial conditions for politics in the post-independence period, a culmination of other factors such as higher segregation, general lack of trust, ethnic voting and clientelism further weakened the political institutions in the former Landlord districts. (see; Alesina & Zhuravskaya (2011), Bardhan & Mookherjee (2012) and, Banerjee & Pande (2007))

While my study provides some useful insights about a colonial institution and its modern day persistence in the politics of India, it should be acknowledged that the IV strategy only allows me to compute the Local Average Treatment Effects (LATE) and hence trace only the first order local effects of a persistent historical variable. Thus, the British policies indeed had far-reaching consequences on the politics of modern India and in many ways have exacerbated the problem in various regions. That being said, the princely states and the other autonomous regions of India, which were indirectly governed by the British crown are outside the scope of the present study and discussed in greater detail by Iyer (2010). Moreover, there are a confluence of factors outside the scope of this study, most notably social media polarisation and promotion of religious hatred and jingoism through popular media, which further provides a fertile ground for the criminals to influence politics. (see; Enikolopov et. al (2011))

References:

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American economic review, 91(5), 1369-1401.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2002). Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. The Quarterly journal of economics, 117(4), 1231-1294.

Alesina, A., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2011). Segregation and the Quality of Government in a Cross Section of Countries. American Economic Review, 101(5), 1872-1911.

Banerjee, A., & Iyer, L. (2005). History, institutions, and economic performance: The legacy of colonial land tenure systems in India. American economic review, 95(4), 1190-1213.

Banerjee, A. V., & Pande, R. (2007). Parochial politics: Ethnic preferences and politician corruption.

Bardhan, P., & Mookherjee, D. (2012). Political clientelism and capture: Theory and evidence from West Bengal, India (No. 2012/97). WIDER Working paper.

Enikolopov, R., Petrova, M., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2011). Media and political persuasion: Evidence from Russia. American Economic Review, 101(7), 3253-85.

Iyer, L. (2010). Direct versus indirect colonial rule in India: Long-term consequences. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 693-713.

Prakash, N., Rockmore, M., & Uppal, Y. (2019). Do criminally accused politicians affect economic outcomes? Evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics, 141, 102370.

Roy, T. (2014). Geography or politics? Regional inequality in colonial India. European Review of Economic History, 18(3), 324-348.